In Brand we trust. Transcultural Global Branding. Starbucks and the meaning of coffee

08.11.2016

1. Introduction

Although there is a growing interest in global consumption issues in the 21st century, relatively little is known about how theoretical frameworks of consumer behavior can be generalized across cultures.

While the word globalization has been around for at least 500 years, Theodore Levitt is famous for coining this term in a Harvard Business Review article that boldly stated, “The globalization of markets is at hand” (Levitt 92). For Levitt, globalization had created a market where uniform products and services could be sold to the masses; however, globalization is now defined as “the worldwide diffusion of practices, expansion of relations across continents, organization of social life on a global scale, and growth of a shared global consciousness” ( Ritzer 160). Much of the books and ideas that currently published on brand identity are known for their lack of a theoretical depth. This lack of depth has led to inconsistent definitions of the concept. I would like to discuss the increased complexities of global branding, e.g. the mobility, displacement and uprooting of people in the age of mass migration leads to more questions about the nature of identity. Nowdays culture is no longer tied to a place or a body of people because more people than ever have access to a global network of information (Rojek 66). Through a vast number of sources – such as the media, technology, internet, advertising, and travel – people discover what it means to be a global citizen.

2. Brands – Big transglobal pictures.

Brands can play an important role in how consumers learn, encode and evaluate product information (e.g., attributes). They can influence consumer evaluations of both relative values of levels and decision strategies or combination rules. In essence, a brand identifies the seller or maker. It can be a name, trademark, logo, or other symbol. A brand is essentially a seller’s promise to consistently deliver a specific set of features, benefits, and services to the buyers. In other words: a brand is even a more complex symbol. For instance, the brand may represent a certain culture. Brand building is image building. Brands have become a central metaphor for both corporate and consumer identity formation. They have led the way to a new form of consumption – mall-based, chain stores and internet shopping showing the homogenised way forward. The semi-spirituality and even quasi-religious overtone of successful brands is discussed. An interesting point is the criticism of business schools and how few of them incorporate design into the management curriculum. Corporate identity has become synonymous with graphic design programmes and therefore to branding itself. Increasingly, corporate and brand image is being recognized as a major influence on sales without a doubt, the concept of branding can fit very well with the idea of the corporate image. Image is at the very core of business identity and strategy. Customers everywhere respond to images, myths, and metaphors that help them define their personal and national identities within a global context of world culture and product benefits. It is proposed that the consumer is involved in a symbolic project whereby they must create meaning out of symbolic materials and that brands are amongst the most powerful of these materials due to their cultural meaning.

Global brand play and important role in that process. The value of Sony, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, VW, and Microsoft is indisputable. Microsoft’s logo pops up on 400 million computer screens worldwide. For many global players such as Royal Dutch/Shell, the trustworthiness of their brand is exhibited through a shell logo that must always appear uniform. The corporation depends on this consistency to connect its 40,000 retail locations in more than 100 countries and to set it apart from competitors. The shell logo signals to consumers that quality is an attribute that can be expected from Royal Dutch/Shell regardless of where the store is located. Increasing preference is being given to a brand that is universally recognizable. Global prominence is attractive to consumers as well as retailers, which is made evident through the powerful leverage of multinational corporations. The emergence of a global citizen requires this level of dedication to branding because people are relying on brands more than ever before to guide their purchase decisions. For many global players such as Royal Dutch/Shell, the trustworthiness of their brand is exhibited through a shell logo that must always appear uniform. The corporation depends on this consistency to connect its 40,000 retail locations in more than 100 countries and to set it apart from competitors. The shell logo signals to consumers that quality is an attribute that can be expected from Royal Dutch/Shell regardless of where the store is located. Increasing preference is being given to a brand that is universally recognizable. Global prominence is attractive to consumers as well as retailers, which is made evident through the powerful leverage of multinational corporations. The emergence of a global citizen requires this level of dedication to branding because people are relying on brands more than ever before to guide their purchase decisions. Ideally a global brand gives a company a uniform worldwide image that enhance efficiency and cost savings when introducing other products associated with the brand name, but not all companies believe a single global approach is the best.

3. Advantages and disadvantages of global branding

3.1 Advantages

What are the advantages of a global brand name? One main advantage is economy of scale in preparing standard packaging, labels, promotions, and advertising. Advertising economies result from using standardized ads and the fact that media coverage increasingly overlaps between countries. Levitt (1983) considers that the economies of scale and scope that a global brand must seek in its standardization process can finally be achieved because of the convergence of consumers across markets. In fact, as global brands standardize their marketing strategy and mix, this generates important cost savings in many areas of their marketing (e.g. R&D, promotion), thus allowing the brand to pour more investments into its marketing efforts and/or to have more competitive prices than its local competitors. Furthermore, with distribution channels going global, global brands seem to have much better bargaining power than local ones. Important international brand equity also allows these brands to better conquer new markets (Douglas et al. 2001), launch new products (Schuiling et al. 2004) and brand extensions (Quelch 1999). In a general way, Hofstede (1980) uses the terms of “mental programming” to emphasise the importance of culture on people’s general behaviour, even though he recognizes the role of individual personality and refutes cultural determinism. Finally, a worldwide recognized brand name is a power itself, especially when the country-of-origin associations are highly respected. Made in Germany raises expectations of quality for certain products and Japanese companies have developed a global reputation for high technology and quality and their names on products give buyers instant confidence that they are getting good value.

3.2 Disadvantages of global branding

On the other side there are also costs and risks to global branding. The overcentralization of brand planning and programming may dissipate local creativity that might have produced even better ideas for marketing the product. Even when a company has promoted its global brand name worldwide, it is difficult to standardize its brand associations in all countries. Heineken beer, for example, is viewed as a high-quality beer in Canada, as a grocery beer in the United Kingdom, and as a cheap beer in Belgium. Thus, a standardized approach on a global scale may not be appropriate, since consumers reinterpret the brand’s marketing actions according to their cultural backgrounds and lenses, in such a way that the brand perception often diverges from the brand expression sent by the firm (Van Gelder 2004). Globalization in its actual state is a complex phenomenon presenting two opposite trends. On the one hand, shared consumption symbols and lifestyles, and the diffusion of the same products, brands and programmes push toward a transnational, global culture. On the other hand, tourism and world media strongly highlight local cultures, customs and lifestyles for which there is more and more growing interest. Thus both the convergent trend for cultural homogenization and the divergent one for cultural heterogenization coexist today and simultaneously influence consumers across the world (Appadurai 1990, Cleveland et al. 2007, Maynard and Tian 2004).

Unilever, for instance is a company that follows a similar strategy of a mix of national and global brands. In Poland, Unilever introduced its Omo brand detergent (sold in many other countries), but it also purchased a local brand, Pollena 2000. Despite a strong introduction of two competing brands, Omo by Unilever and Ariel by Procter&Gamble, a refurbished Pollena 2000 had the largest market share a year later. Unilever’s explanation was that East European consumers are leery of new brands; they want brands that are affordable and in keeping with their own tastes and values. Pollena 2000 is successful not just because it is cheaper but because it chimes with local values.

4. Case Studie: Starbucks and the Meaning of coffee

4.1 Introduction

The nature of the product or service offered by an international brand has a considerable impact on its capacity to standardize its marketing - or on the contrary on the necessity to adapt it. Product category is thus one of the most cited determinants of the standardization strategy in the different articles and frameworks (e.g. Alden et al. 1999, Quelch 1999, Theodosiou et al. 2003). Moreover, Hassan et al. (2003) consider that not all product categories show the same global potential, and recommend that international marketing strategies should strongly take this into consideration. Thus, the more a brand operates in a product category with strong global vocation, the more it could easily standardize elements of its marketing. In recent times, it seems as though the consensus is to use a creative – yet consistent – image that can be easily translated across borders. In other words, a centralized approach to marketing is what builds the brands with greatest recognition around the world today. There are corporations ranging from IKEA to Starbucks that have been “able to defy cultural and linguistic differences and appeal to people in numerous locations and societies” (Byrnes 2007) by promoting a single worldwide identity.

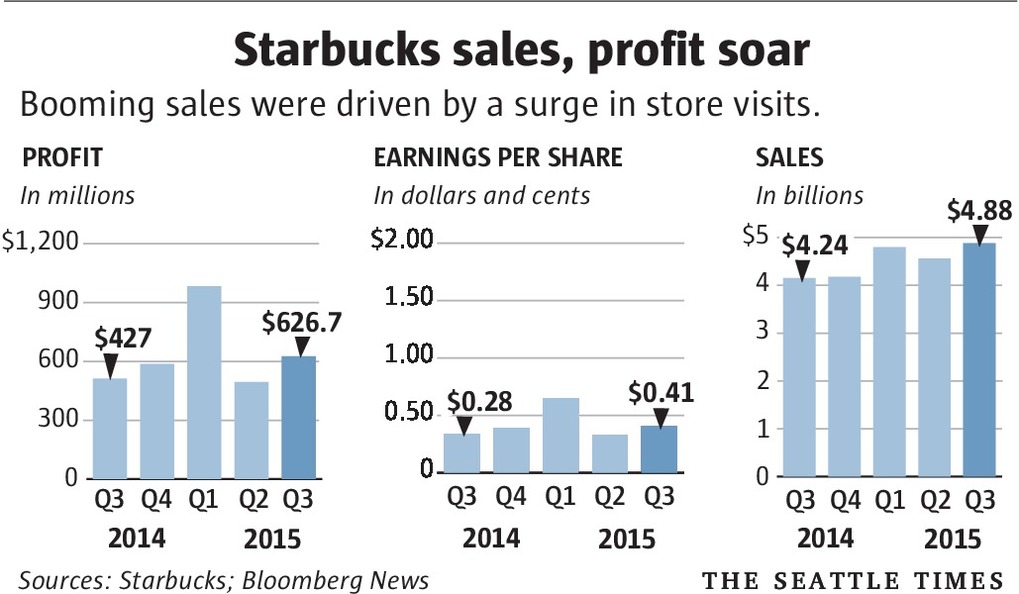

4.2. The Success of Starbucks

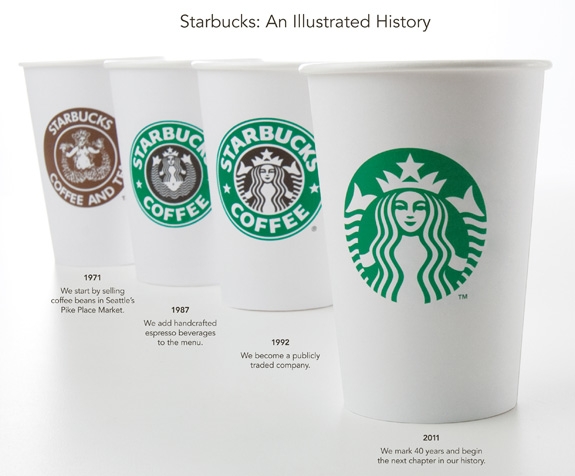

Founded in 1971, Starbucks is now the largest coffee chain operator in the world, with more than 15,000 stores in 44 countries, and in 2007, accounted for 39% of the world’s total specialist coffee house sales .

In North America alone, it serves 50 million people a week, and is now an indelible part of the urban landscape.

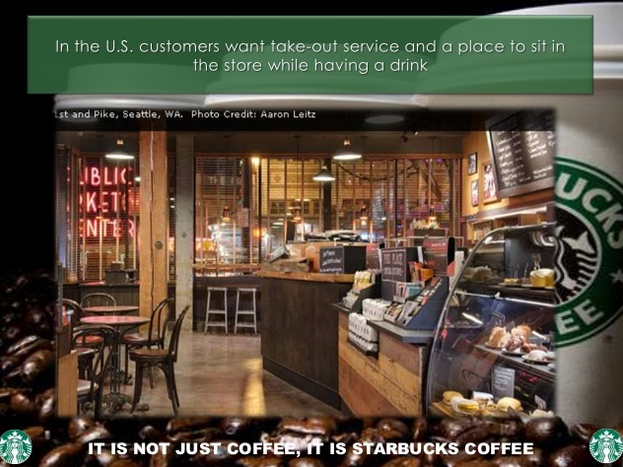

But just how did Starbucks become such a phenomenon? Firstly, it successfully Americanised the European coffee tradition. Secondly, Starbucks did not just sell coffee – it sold an experience. As founding CEO Howard Schultz explained, ‘‘We are not in the coffee business serving people, we’re in the people business serving coffee” (Schultz and Yang, 1997). This epitomised the emphasis on customer service such as making eye contact and greeting each customer within 5 seconds, cleaning tables promptly and remembering the names of regular customers. From inception, Starbucks’ purpose was to reinvent a commodity with a sense of romance, atmosphere, sophistication and sense of community (Schultz and Yang, 1997). Next, Starbucks created a ‘third place’ in people’s lives – somewhere between home and work where they could sit and relax.

All this came with a premium price. While people were aware that the beverages at Starbucks were more expensive than at many cafés, they still frequented the outlets as it was a place ‘to see and be seen’.

In this way, the brand was widely accepted and became, to an extent, a symbol of status, and everyone’s must-have accessory on their way to work. So, not only did Starbucks revolutionise how Americans drank coffee, it also revolutionised how much people were prepared to pay. A symbol of status and a symbol of recognition and trust Like McDonald’s, Starbucks claims that a customer should be able to visit a store anywhere in the world and buy a coffee exactly to specification. This sentiment is echoed by Mark Ring, CEO of Starbucks Australia who stated ‘‘consistency is really important to our customers . . . a consistency in the product . . . the overall experience when you walk into a café . . . the music . . . the lighting . . . the furniture . . . the person who is working the bar.” (Patterson et al 2010) So, whilst there might be slight differences between Starbucks in different countries, they all generally look the same and offer the same product assortment. Together, all these parameters create a consistent image in the heads of the consumers.

4.3 The Australian coffee culture

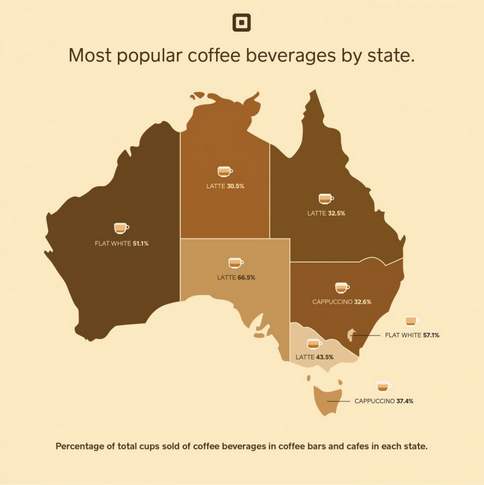

It is fair to describe Australia’s coffee culture as mature and sophisticated, so when Starbucks entered Australia in 2000, a thriving urban café culture was already in place.

For Australians, coffee is as much about relationships as it is about the product, suggesting that an impersonal, global chain experience would have trouble replicating the intimacy, personalisation and familiarity of a suburban boutique café. Furthermore, through years of coffee drinking, many Australians, unlike American or Asian consumers, have developed a sophisticated palate, enjoying their coffee straighter and stronger, and without the need to disguise the taste with flavoured, syrupy shots. Coffee drinkers in Australia are discerning, and they will go out of their way to purchase a good cup of coffee. They are not as easily persuaded as people from other countries simply to visit their nearest café. Secondly, for a café to make a profit, it needs to turn over 15 kg of coffee a week. The national average is 11 kg, so a café has to be above average to begin with to even make a profit.

4.4 The decline of Starbucks in Australia

Starbucks has since been harshly criticised by Australian consumers and the media. Their coffee has been variously described as ‘a watered down product’, ‘gimmicky’, and consisting of ‘buckets of milk’. These are not the labels you would choose to describe a coffee that aspires to be seen as a ‘gourmet’ product. It has also been criticised for its uncompetitive pricing, even being described as ‘‘one of the most over-priced products the world has ever seen” (Patterson et al, 2010). By not offering a better experience and product than emerging direct competitors, Starbucks found itself undermined by countless high street cafés and other chains that were selling stronger brews at lower prices and often offering better or equal hospitality. Whilst they may have pioneered the idea of a ‘third place’, it was an easy idea to copy, and even easier to better by offering superior coffee, ambience and service. Now, with so many coffee chains around, Starbucks have little point of differentiation, even wi-fi internet access has become commonplace across all types of café. Furthermore, some would argue that Starbucks has become a caricature of the American way of life and many Australians reject that iconography. Many are simply not interested in the ‘super-size’ culture of the extra-large cups, nor want to be associated with a product that is constantly in the hands of movie stars.

Instead, they maintained that their stores are the core of the business and that they do not need to build the brand through advertising or promotion. Howard Shultz often preached, ‘‘Build the (Starbucks’) brand one cup at a time,” that is, rely on the customer experience to generate word-of-mouth, loyalty and new business.

5. Conclusion

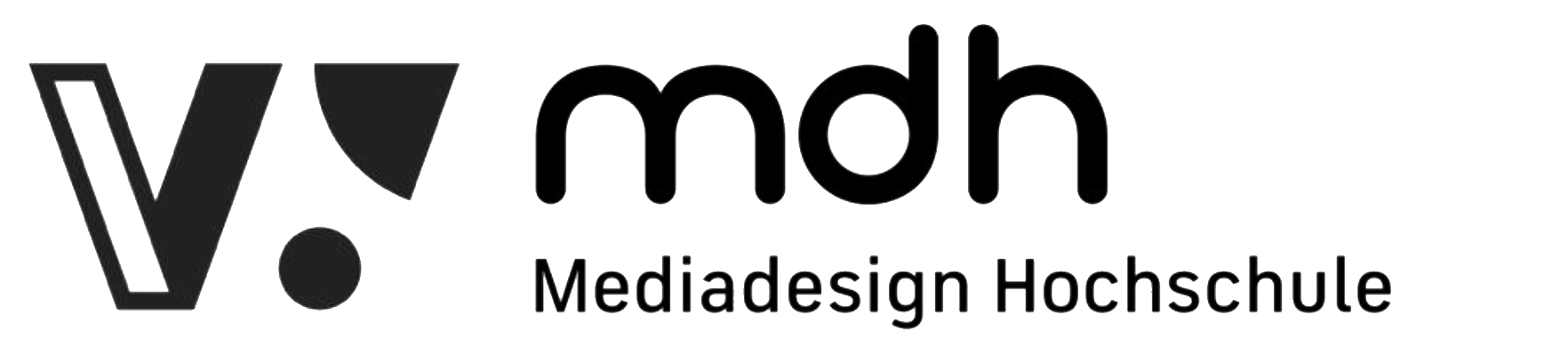

By only considering the effects of one culture on their consumers, international brands risk failure (Firat 1997). The rigid dichotomy between total standardization and total adaptation of the marketing options of an international brand - that Buzzell (1968) considers as neither feasible nor desirable – becomes therefore obsolete. Instead, researchers recommend considering intermediate solutions combining both options when developing international marketing strategy. A glocal marketing strategy is certainly a far more realistic option than a local or a global one for most international brands. That raises the important question which elements of the marketing strategy can or should be standardized, and to what degree? These complex analysis frameworks have in common the idea that adapting or standardizing international marketing is not a dogmatic decision. As the example of Starbucks – amongst others – has shown, it is important to have a mix of standardization and adaptation. That “brand mix balance” corresponds to an analysis of the brand, its history, its public, its markets and its micro- and macro-environments, also known as the contingent factors at a given time on a given market (Theodosiou et al. 2003).

References

- Alden, D. L., Steenkamp, J. B. E., & Batra, R. (1999). Brand positioning through advertising in Asia, North America, and Europe: The role of global consumer culture. The Journal of Marketing, 75-87.

- Appadurai, A. (2011). Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy 1990. Cultural theory: An anthology, 2011, 282-295.

- Buzzell, R. D. (1968). Can you standardize multinational marketing?. Reprint Service, Harvard business review.

- Byrnes, K. The Sharing of Culture: Global Consumerism. http://www.uwlax.edu/URC/JUR-online/PDF/2007/byrnes.pdf (Zugriff am 17.10.2016)

- Cleveland, M., & Laroche, M. (2007). Acculturaton to the global consumer culture: Scale development and research paradigm. Journal of business research, 60(3), 249-259.

- Douglas, S. P., Craig, C. S., & Nijssen, E. J. (2001). Integrating branding strategy across markets: Building international brand architecture. Journal of International Marketing, 9(2), 97-114.

- Fuat Firat, A., & Shultz, C. J. (1997). From segmentation to fragmentation: markets and marketing strategy in the postmodern era. European Journal of Marketing, 31(3/4), 183-207.

- Hassan, S. S., Craft, S., & Kortam, W. (2003). Understanding the new bases for global market segmentation. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 20(5), 446-462.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 10(4), 15-41.

- Levitt, T. (1983), “The Globalisation of Markets”, Harvard Business Review May/Jun. Cited in de Wit, B & Meyer, R, (1998), “Strategy Process, Content Context, an International Perspective” 2nd Ed, West. Pp 733-741.

- Maynard, M., & Tian, Y. (2004). Between global and glocal: Content analysis of the Chinese web sites of the 100 top global brands. Public Relations Review, 30(3), 285-291.

- Patterson, P. G., Scott, J., & Uncles, M. D. (2010). How the local competition defeated a global brand: The case of Starbucks. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 18(1), 41-47.

- Quelch, J. (1999). Global brands: Taking stock. Business Strategy Review, 10(1), 1-14.

- Ritzer, G. (2007). The globalization of nothing 2. Sage.

- Rojek, C. (1997). Touring cultures: Transformations of travel and theory. Psychology Press.

- Schuiling, I., & Kapferer, J. N. (2004). Executive insights: real differences between local and international brands: strategic implications for international marketers. Journal of International Marketing, 12(4), 97-112.

- Schultz, H., & Jones Yang, D. (1999/1997). Pour your heart into it: How Starbucks built a company one cup at a time. Hyperion.

- Theodosiou, M., & Leonidou, L. C. (2003). Standardization versus adaptation of international marketing strategy: an integrative assessment of the empirical research. International Business Review, 12(2), 141-171.

- Van Gelder, S. (2004). Global brand strategy. Journal of Brand Management, 12(1), 39-48.